Week 1: introduction

Outline

In this week’s lab you will:

- get your microbit and connect it to the computer

- create your first program using the VSCode IDE

- compile, run and debug your first program

- learn how to submit lab work on GitLab

Introduction

Welcome to the COMP2300 labs! These labs are the heart of the course, and they’re your opportunity to learn the core concepts by putting them into practice. They are also your chance to explore and ask questions. If you don’t understand all of what’s going on in this lab, that’s ok—for two reasons:

- this is just the first lab (and it’s in week 1, not week 2 which is the case for some other courses), so we’ll cover all this stuff in detail in both lectures and future labs

- there are no stupid questions in this course, so the lab sessions are the time to speak up

The labs for this course have a few different recurring parts, and they will be presented using different coloured boxes:

General notes & information will be highlighted in a blue box.

Sometimes you need to think about stuff before you go ahead. If you see something in a pink box (because your brain is pink—sortof), that’s your clue to pause and think—how do you expect the next part will work? Take a moment to think before you blaze away and start coding, because then you can check whether you really understand what’s going on or whether you’re just copy-pasting stuff without really understanding it. If you don’t understand it perfectly, that’s ok—ask your lab neighbour, or your lab’s Teams chat (or your tutor directly) to help you understand.

These lab sessions, whether in-person or online, will give you plenty of chances to discuss things with other people in your lab group. If you see a green box, read it and talk about the prompt with someone in your group–if you’re in person you’ll need to remember to keep a responsible distance, and if you’re online your tutors will explain how to start a discussion in Teams.

In this course, as in most (all?) others, your fellow students are your best resource. Between you, you might not know the answer straight away, but together you might find that you can work it out. If you can’t, then of course you can ask your tutor—but your tutor might not be able to help you immediately. This also means that if you’re helping one of your fellow students understand something, put yourself in their shoes. It takes courage to ask a question, especially if you feel like everyone else in the lab knows what’s going on (although that certainly isn’t true). Be gentle and helpful in your answers, and remember that you can be honest about stuff that you don’t know—you’re all on this journey together.

All assignment & lab submissions in this course happen through GitLab. You are expected to push your lab work up to our GitLab server at various stages during your lab to get your lab marks. An orange box clearly indicates that something you have been working on needs to be committed and pushed to GitLab in order to be considered “done”.

These coloured boxes will be used consistently through the lab material, so take a moment to familiarise yourself with what the different colours mean, or at least remember that you can come back here and check at any time.

Task 0: setting up the COMP2300 software environment

Setting things up deserves its own page. Go read this page, see you back here when you’re done :)

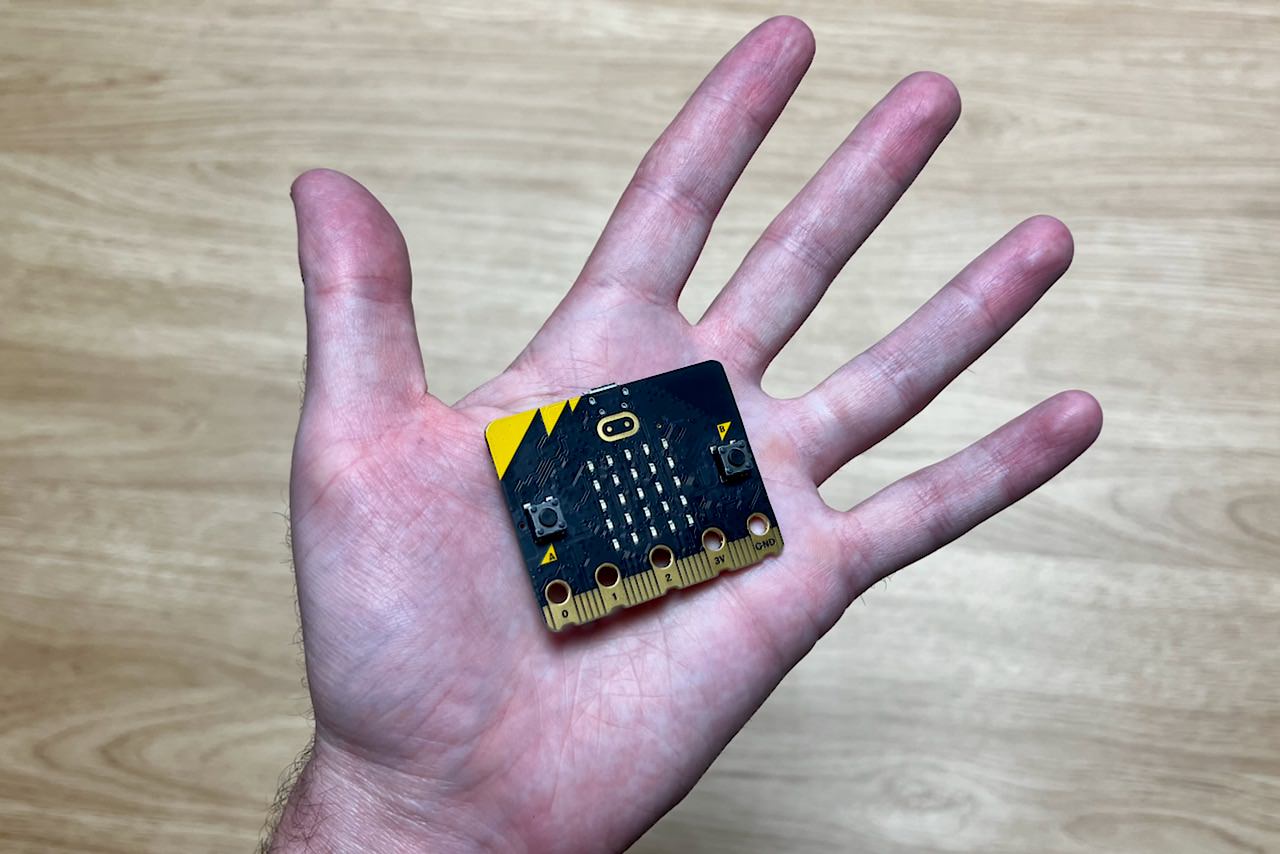

Task 1: getting your microbit

If you’re online, we’ll let you know how you can get your own microbit in the week 1 lectures. For now you’ll be using the “microbit emulator”, which is a piece of software that works in the exact same (well, sort of) way as a physical board–how to use it is explained a bit later in the lab. If this is you, skip to exercise 3.

If you’re in-person, during this lab the tutors will come around and give you a microbit and USB cable of your very own—this is yours to keep forever. How exciting! The only caveat is that if you unenroll from the course before the census date you will have to give it back.

Handing all the boards out might take a bit of time, though, so thanks for your patience. While you’re waiting, push your chair away from the desk, turn, and say hello to the person next to you. Introduce yourself. Find out what degree they’re taking, and why they’re taking this course—is it a prerequisite or an elective? If you’re feeling extra-personable, ask what they like to do in their spare time. (If they’re already your friend, find someone else who you don’t know and talk to them instead.)

Task 2: connecting the microbit to the computer

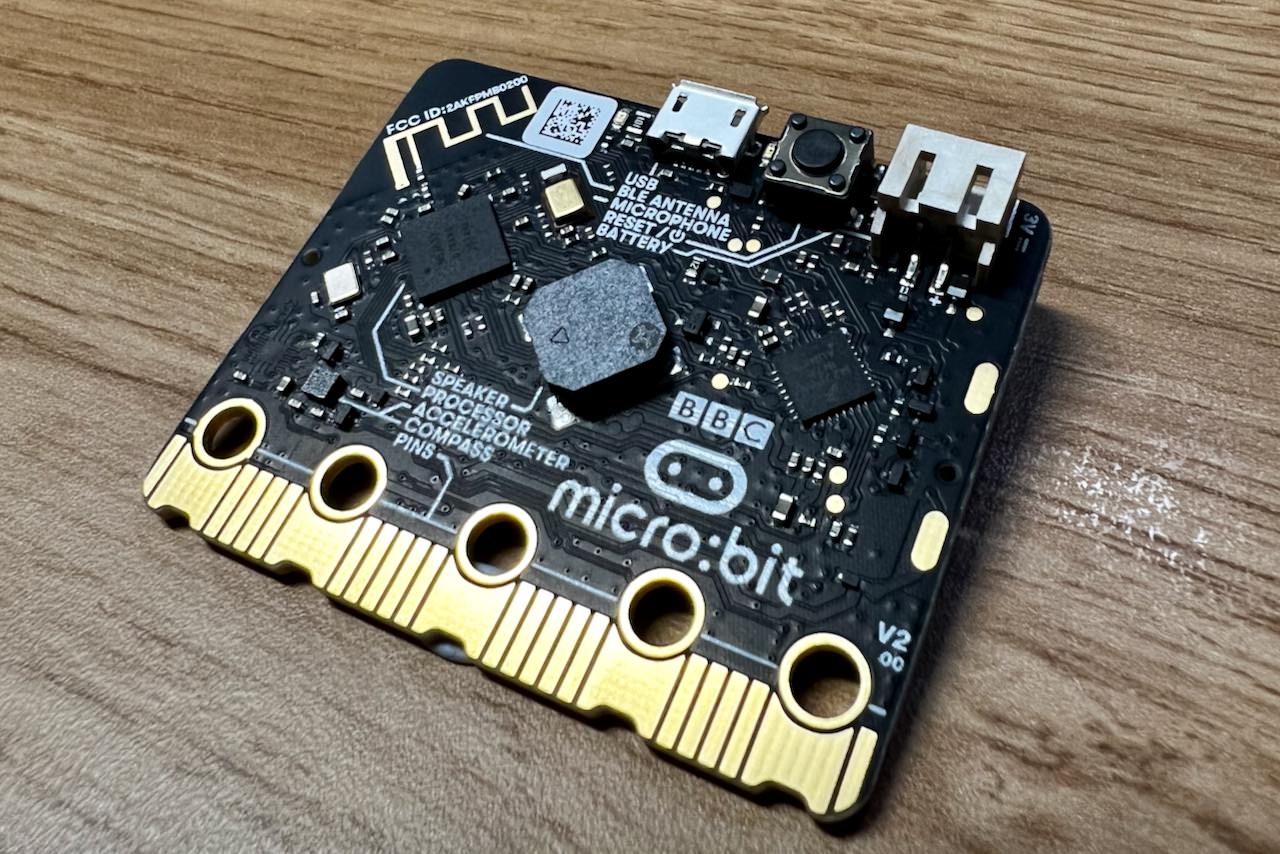

The microbit connects to the lab computer (or your personal laptop) via a micro-USB cable.

Your microbit isn’t super fragile, but you’ll still need to be careful when carrying it around. Here are a few tips:

- pack the board up in its bag/box when you’re not using it

- make sure the USB cable is unplugged before putting into your bag

Once you’ve received your new microbit, plug it in to the lab computer—the full-size USB end goes into the lab computer, and the small end of the USB cable goes into the connector at the top edge of your microbit.

You’ll find at this stage that your microbit starts playing a little default program. Feel free to enjoy the little game/demo that comes on it, you’ll have to erase it in a minute!

Task 3: your first microbit program

With your lab neighbour, open up the main VSCode documentation website. Discuss with them: what makes a good documentation website?

Now that you’ve connected your board to the computer it’s time to turn everything on and see if it works. This exercise is a bit longer, so it’s broken down into stages: clone, edit, build & run.

Fork & clone

In this course, you’ll be using git a lot, and you’ll have a lot of git

repositories (repos for short). Don’t fear: you’ve done this before (in the

pre-requisites for this course) and it’s the same process here. Since we’re at

the start of the course, here’s a tip: it’s a good idea to make a comp2300

(or comp6300) directory somewhere on your computer where you can keep all

of your stuff for this course.

Ok, now here goes:

- fork the labs 1-3 template repo to your user account (i.e.

uXXXXXXX) - clone it to your local machine

You can do the git clone step in the terminal, or your favourite git client,

it doesn’t matter. If you like, you can use VSCode’s built-in git support:

here’s a link to the general docs on this

view,

and here’s the specific instructions on how to clone a

repo.

Remember, this is all stuff you learned in COMP1100. We’ll make sure we help you out if you’re a bit rusty, but make sure you can fork, clone and (at the end) push to GitLab—you won’t be able to submit the assessment items any other way.

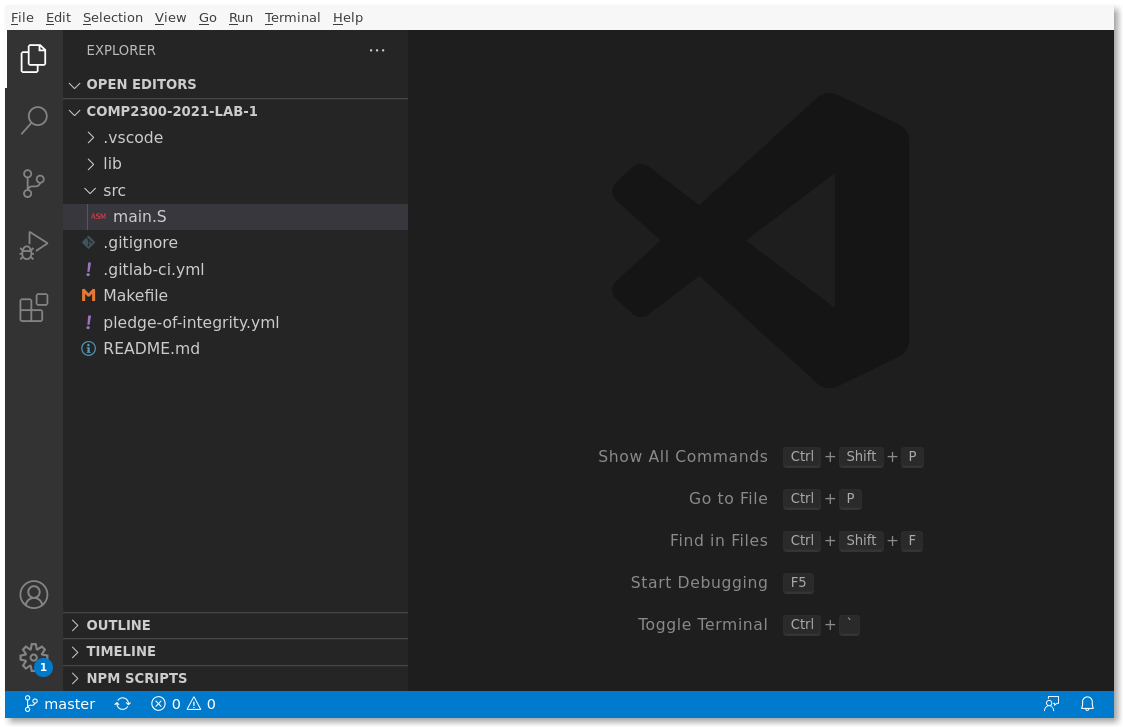

Once you’ve cloned down the repo, you must make sure to open the week-1 sub-folder.

You can do this in VSCode by doing File -> Open Folder... -> week-1. If you don’t open

a sub-folder, the COMP2300 VSCode extension won’t know how to build your code.

Once you’ve done that you should see something like this:

Again, the VSCode docs have a good explanation of the user interface.

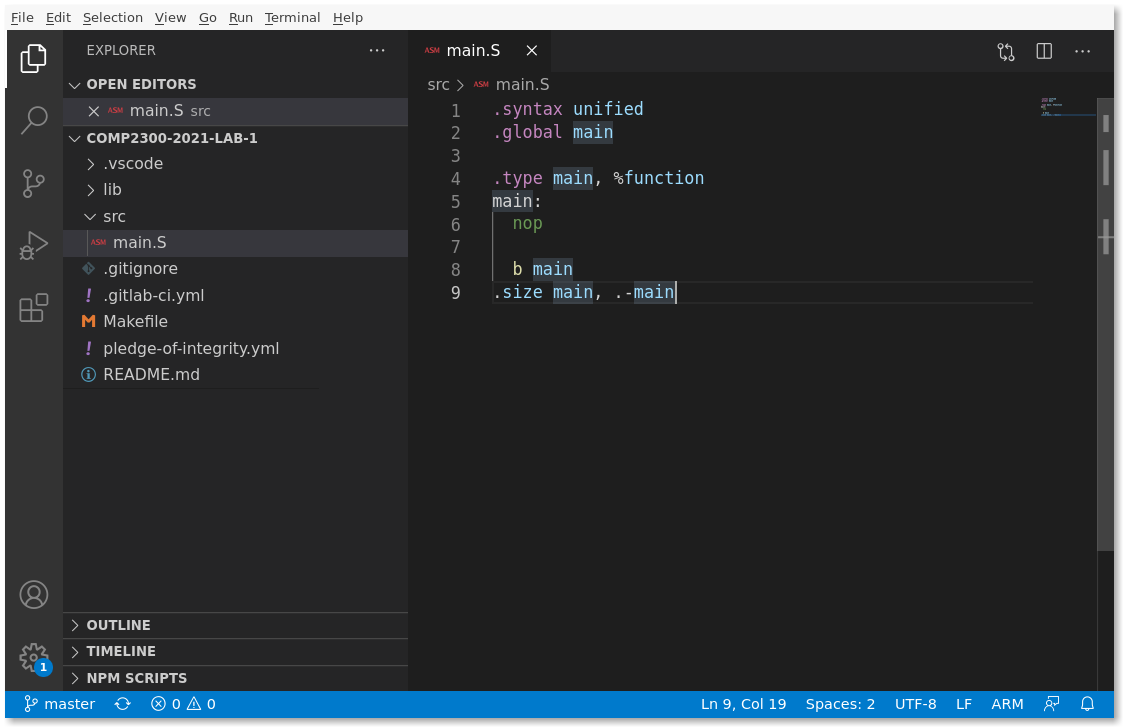

Now, in the Explorer view, open the src/main.S file, you should see

something like this:

Even if you’ve never seen any assembly language before, what do you think this program does?

Edit

Add some code so that main.S looks like this:

.syntax unified

.global main

.type main, %function

main:

mov r1, 0

loop:

add r1, 1

b loop

Save the file when you’re done. Don’t worry if you don’t understand all the details at this stage—the goal for this week’s lab is just to plug things in, turn them on, and make sure that everything’s working. If you have any problems, let your tutor know now.

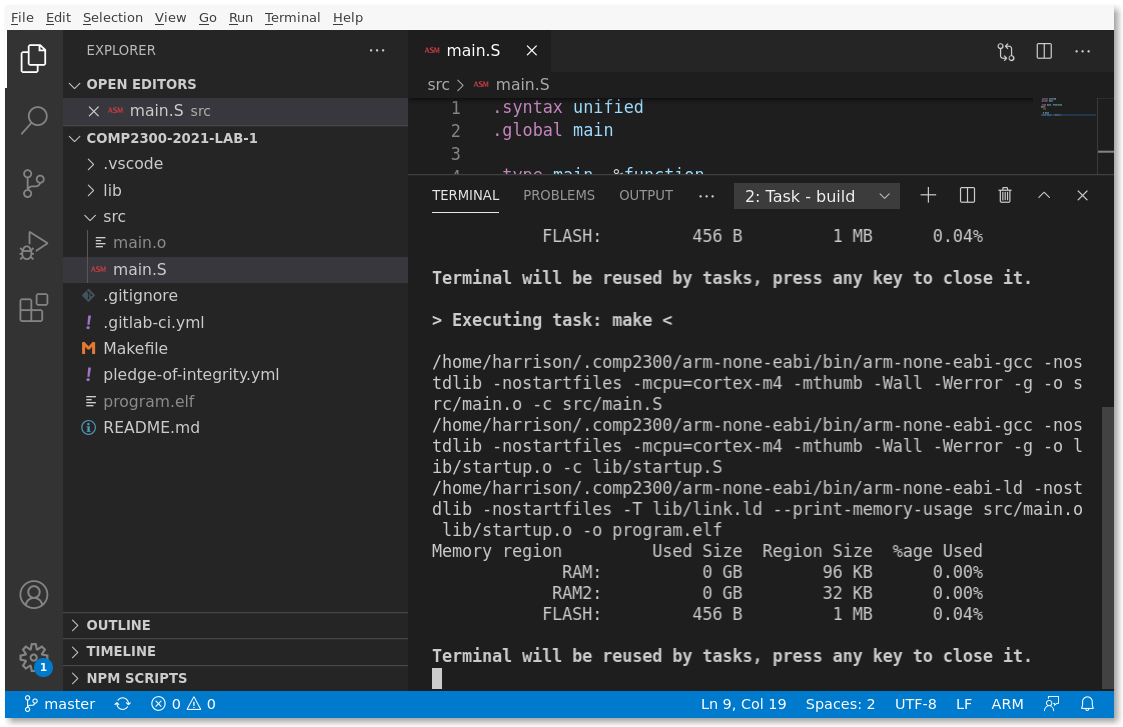

Build

You can build (or compile—they mean the same thing in this context) your

program using the Build command (COMP2300: Build in the command

palette).

You’ll see some stuff printed to the

terminal (near

the bottom of your VSCodium window), and when it’s done it should look something

like this:

The compilation process takes all the code (text files), translates them into binary instructions for the target Instruction Set Architecture (ISA)— ARMv7 in this case—and links them together into a binary file (image). You can learn more about it here if you want to read ahead, but you’ll also get familiar with it throughout this course.

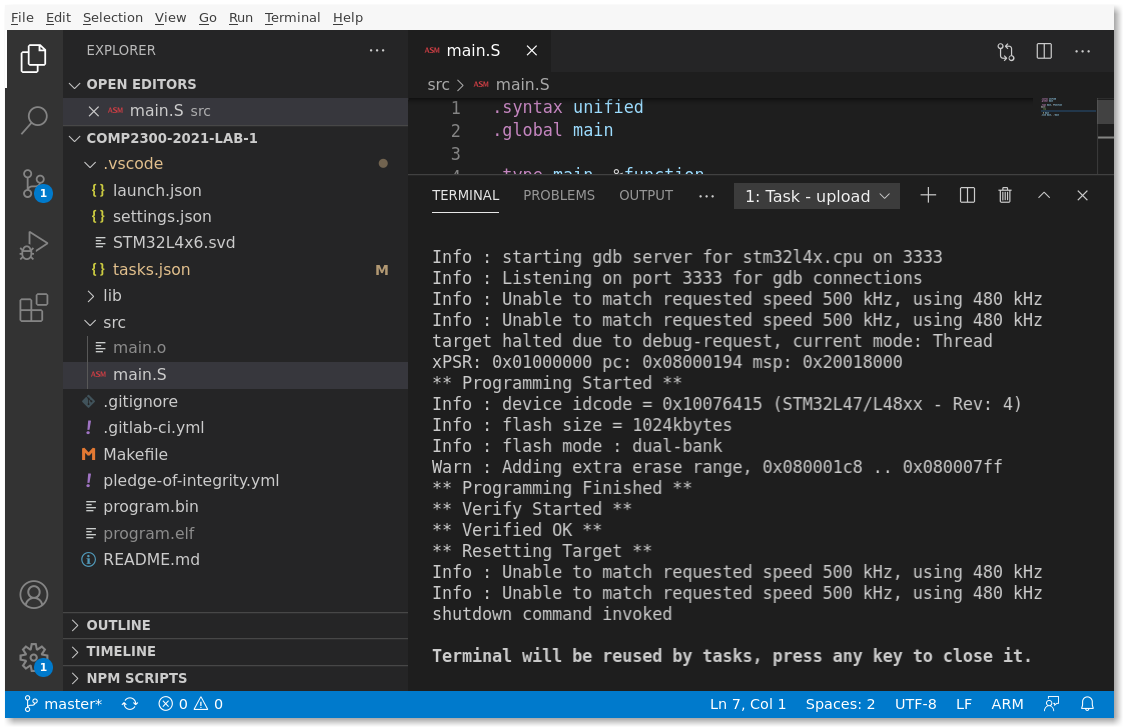

Upload

If you’re a remote student without a microbit, skip to the next step :) You’ll learn how to get programs onto the emulator there.

You’ve built the program on your laptop/desktop. To run it on your

microbit you need to upload it with the Upload (COMP2300: Upload)

command. Again, afterward it should look something like this:

If you get errors at this point, then they’ll be printed (probably in red) in the terminal. Try and figure out what’s going wrong yourself, also checkout the troubleshoot section in software setup

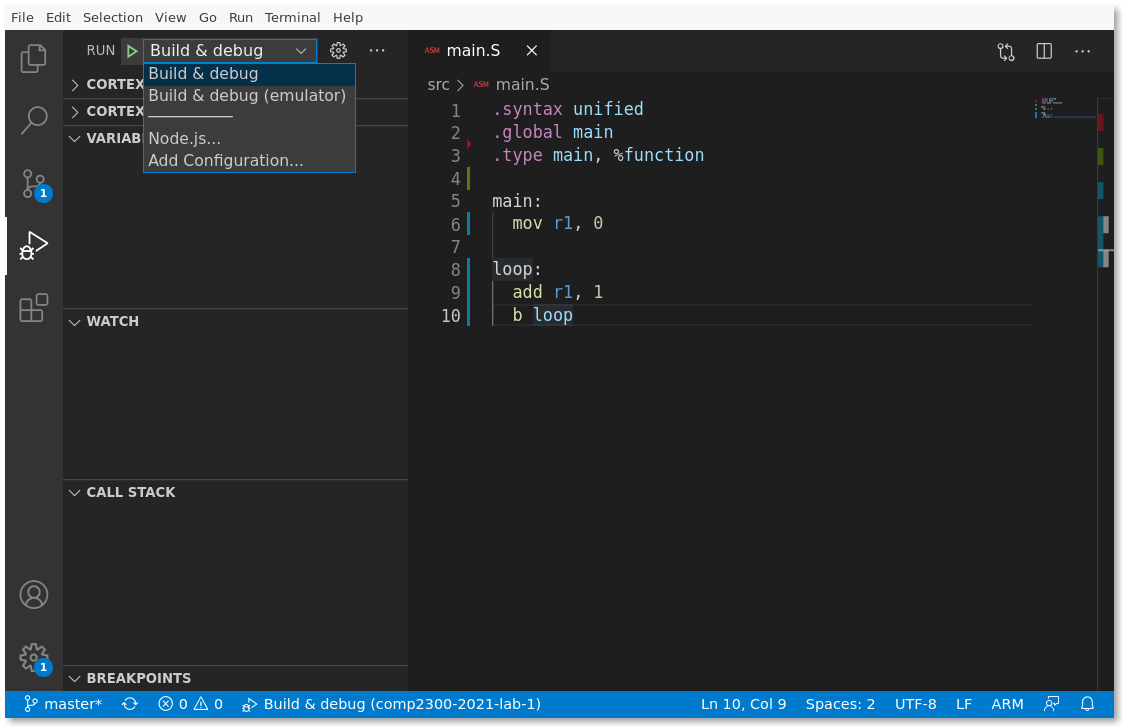

Run & Debug

When you upload your program to the microbit, it starts running it automatically.

To debug the program (stepping it through, inspecting the CPU & memory states), we’ll use VSCodium’s built-in debugger—an invaluable tool for making things work right when we’re writing programs for the microbit. You may have used a debugger like this before, or you may not have—that’s ok! We’ll lead you through the basics in the labs over the next couple of weeks.

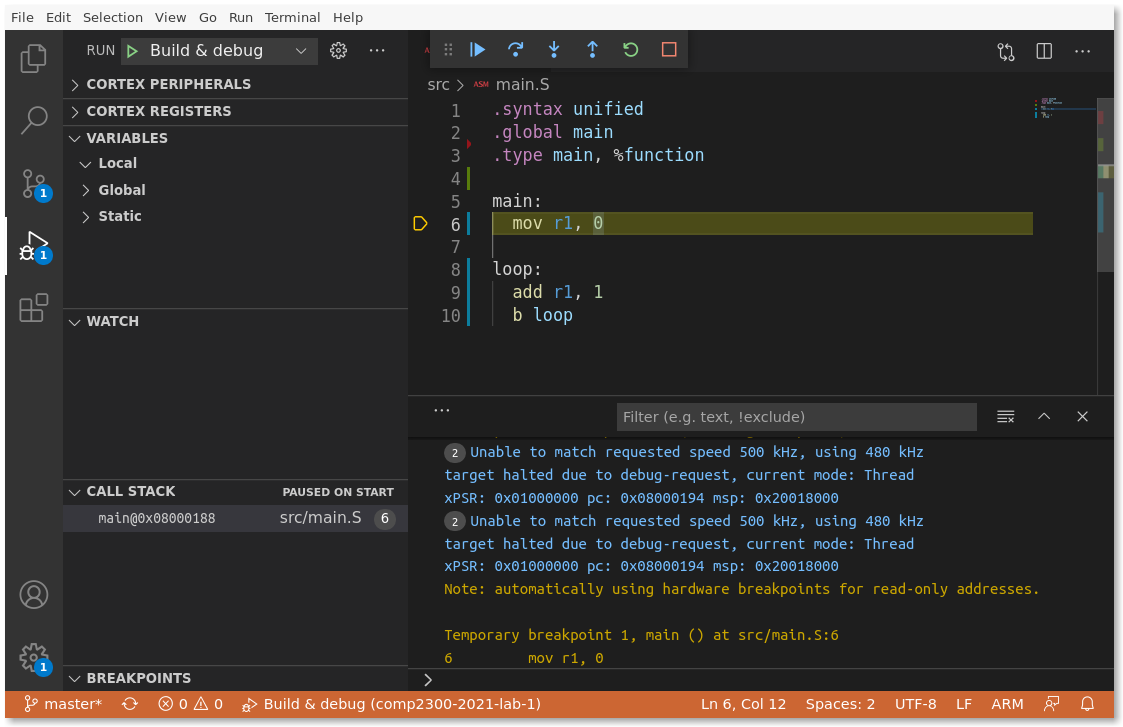

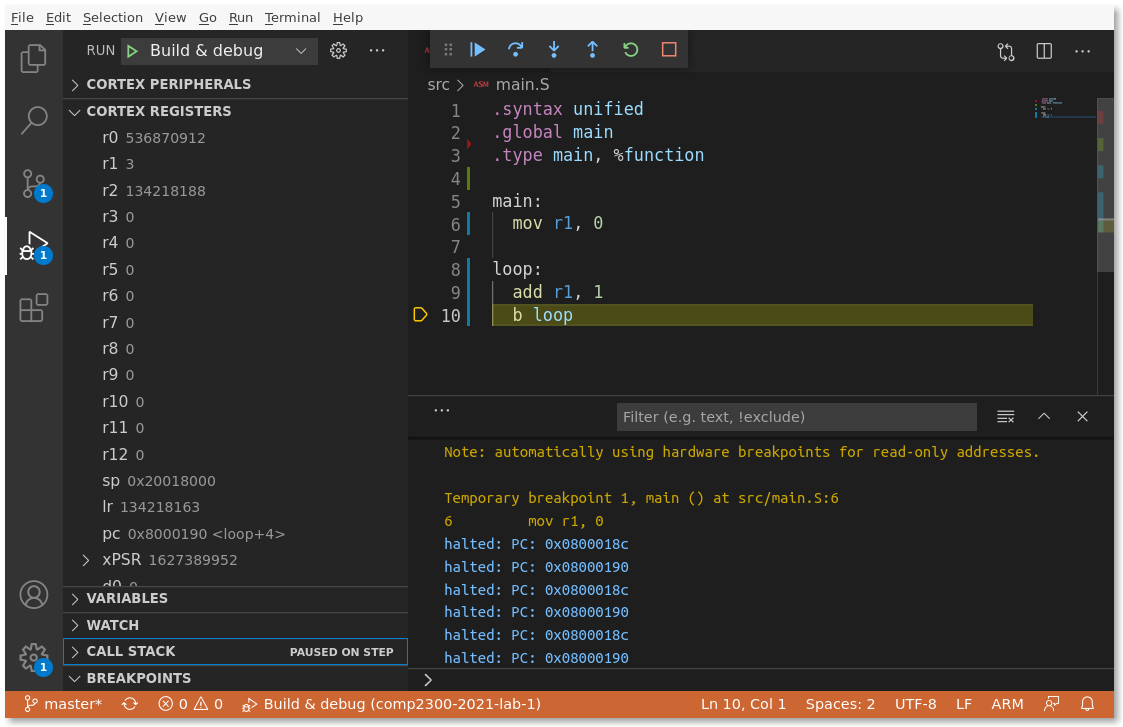

Open up the Debug view and make sure “build & debug” is selected (if you are a remote student wanting to use the emulator, select “build & debug (emulator)”).

Click the green play button to run your program, pausing (“breaking”) on entry.

The highlighted yellow line of assembly code (shown in the above screenshot)

represents where the program is “up” to (next instruction to execute).

When you first start it running, the

IDE creates a breakpoint at the

main: label in your program, so when your program reaches that line of code it

stops and waits for further instructions (from you!).

At this point, you can step through the code one instruction at a time using the debug controls:

Discuss with your lab neighbour—what do all these debug control buttons do? Play around with them together—can you see what effect they’re having on the program executing on your microbit? Are you pumped?

If you want your program to keep running (i.e. to “unpause” the program) just hit the blue play button (although it’s called continue rather than play when you’re debugging, because it continues after you last paused the execution). Once it’s running, you can pause it again by hitting the pause button, and even stop it with the red stop button.

Once it’s stopped, you can restart the whole process again in a new debugging session by going back to the start of these instructions.

Sometimes the debuggers are a bit flaky, and get into some problems. You’ll get the hang of recognising when things have gone wrong & how to fix them. Remember that it’s ok to use the stop or restart buttons to try and get things back on track, or (worst-comes-to-worst) unplug and re-plug your microbit.

You can also examine the values of your registers in the REGISTERS viewlet under the Debug View (see the bottom left corner in the below screenshot):

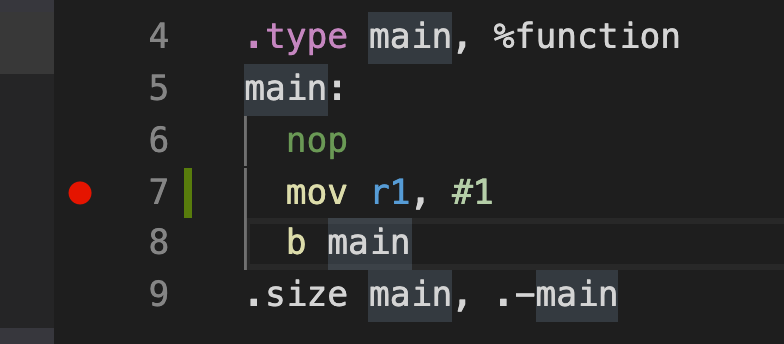

If you want to control exactly where the system pauses for debugging, you can set a new breakpoint by clicking in the left-hand “gutter” (or margin) of the code view in the IDE. You should see a little red dot appear:

The program isn’t running on the lab computer on the desktop (well, unless you’re using the emulator… if you are then ✨imagine✨!)—it’s running on your microbit. What does that mean? What are the implications for the way you run & debug your program?

Now that you have verified that you can edit, build, and debug a

microbit program, copy the code into tasks/task-3.S. Commit and push your changes with the message “completed task 3”.

Task 4: CI

In GitLab, there is a feature called Continuous Integration (CI). It’s basically a set of “jobs” (builds & tests) to run everytime you push something to your repo, to make sure that your commit doesn’t break the build.

In COMP2300 we use CI to do some basic testing to help you make sure that your code builds fine, and you have satisfied some basic requirement for the lab/assignment.

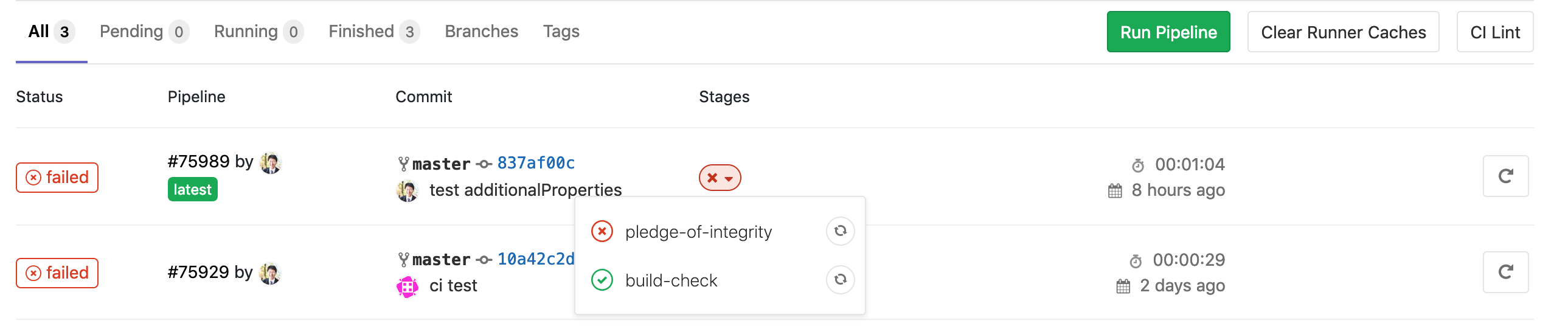

You can see the CI pipelines and build jobs at the “CI / CD” sidebar in your GitLab repo. After clicking on it, you will see a page like this:

You can see the jobs run by clicking on the Stages dropdown button, and whether they are successful of not. You can click on the job to see the details and captured output, which will help to figure out what might have gone wrong.

In lab 1, we only have one coding task (task 3). At the end of that task you copied your code into a file in the task folder called task-3.S. The CI job will check that code exists and builds. In later labs you will have several coding tasks and need to copy code into multiple files. This gives you and us a way of keeping track of the tasks you have completed.

It’s really important to know that CI jobs are not instantaneous. They actually have to run on a computer and can take time to work. Crucially, there’s only a limited number of computers (called CI “runners” because they… run jobs..) so your CI job might go into a queue. The queue can be quite long when a bunch of student all run jobs together (e.g., at the end of a lab or on the due date of an assignment) and the CI runners sometimes crash for some reason and need to be rebooted, so if you see your job is “pending” or “running”, you will have to wait.

Have you read the above information about “pending” or “waiting” for CI jobs? Here’s the warning: you will see this during the course, so try not to be frustrated when it happens. The good news is that if you commit and push code to GitLab it counts as submitted even if CI jobs are still pending.

We have set up the CI jobs in your lab repository to correspond to task 3. As explained above, check the jobs for the latest commit. Are there any crosses? (You might have to wait a while for your jobs to be completed). If you see only a tick for the week 1 lab, then you have completed your tasks for today!

Extra Tasks

There’s no specific extra content this week. Having said that, the microbit is now yours, so you can program it however you like—especially since you can install the IDE on your own laptop/desktop.